How To Create A Weather Forecast Website

Earlier this week, the situation for New Yorkers looked dire. A blizzard was coming. Maybe the biggest blizzard in New York City's history. The subway was shut down for the first time ever because of snow, highways in the tri-state area were closed, and residents were warned to stay indoors. And then: nothing. There was snow in the city and across the east coast, but the blizzard didn't come close to what weather forecasters had predicted.

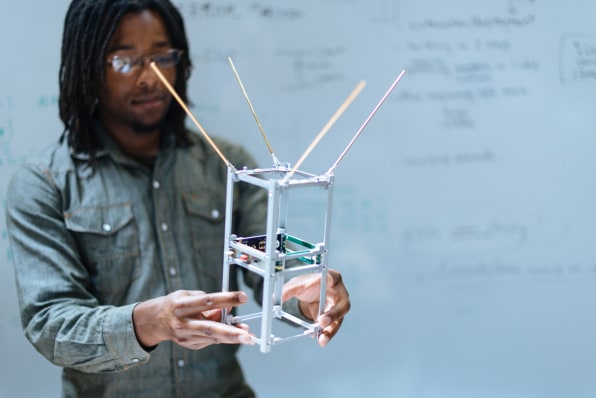

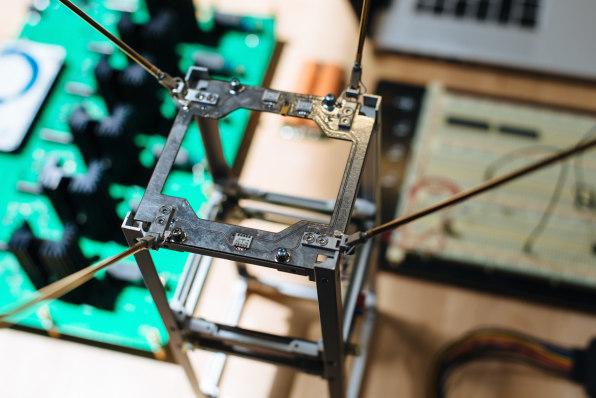

Peter Platzer, the CEO of a new satellite data startup called Spire, thinks the whole overblown mess could have been avoided. His company is launching over 100 shoebox-sized satellites–called CubeSats–that use a technology called GPS Radio Occulation to generate 10,000 weather condition readings each day. Today's large, billion-dollar weather satellites only provide 1,500 readings each day, and fewer than 20 of these large satellites are currently in orbit.

"While we have reasonable amount of [weather] data over land from satellites, drones, cell phones, and so on, we lack that kind of density over the oceans. That gap over the oceans is one of the single biggest challenges that weather forecasters face," says Platzer. Spire's satellites will cover the entire earth, including the oceans.

There are other startups launching CubeSats, including Planet Labs and Skybox (now part of Google). But their satellites are focused on collecting imagery from space, while Spire's data isn't image-based–instead, the company collects weather-related data, like temperature, pressure, and moisture.

There are a number of differences from traditional car-sized, pricey weather satellites, beyond size and cost (Platzer won't give specifics on cost, but says his satellites are "significantly cheaper than tens of millions or millions of dollars"). Since traditional satellites are designed to last a decade, they rely on old technology that can't be updated remotely; some still use the technology equivalent of the 486 PC, released in 1989. And a number of these satellites are expected to start failing in 2016, potentially leading to a weather data gap that lasts up to four years.

Spire's satellite software, in contrast, is upgradeable over the air. The company also plans to replace a quarter of its satellite constellation with newer hardware every six months. "We are like the iPhone of space," he says.

Platzer stresses that Spire isn't out to replace the weather satellites from agencies like NASA and NOAA. "It's not an either/or approach. Our advantage is phenomenal data coverage and system resilience," he says. "At the same time, there are complex and power-hungry applications that you can only do from single point of failure billion dollar satellites. It's a partnership."

Spire will send its satellite constellation this fall, hitching a ride as cargo on other launch vehicles with planned trips into space (much like the other CubeSat startups have been doing). The company has already signed over a dozen contracts in the public and private sector for its data, which could be useful for any number of industries, including power, insurance, agriculture, and of course, general weather forecasting.

How To Create A Weather Forecast Website

Source: https://www.fastcompany.com/3041607/this-companys-tiny-satellites-could-finally-make-weather-forecasting-more-accurate

Posted by: baileylierearmeng.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How To Create A Weather Forecast Website"

Post a Comment